You might not think, at first, that antique plastic radios belong in an art museum’s collection. But after you see the new exhibition, “Art of the Airwaves: Radios from The Hilbert Collection,” at the Hilbert Museum of California Art through August 7, you might think again.

This stunning ensemble of 22 shelf radios and one floor radio from the “Golden Age of Radio” —the 1930s to the 1950s— spotlights the fact that during those decades, many of America’s finest industrial designers were creating the sleek, sophisticated looks of the nation’s most popular radios.

Radio, of course, was the world’s most widespread broadcast medium during most of the early to mid-20th century. Along with newsreels in the cinemas and popular magazines and newspapers, radio was how most citizens received the most immediate news of the world. Along with that, national and local radio broadcasts provided reliable entertainment in the home. Listeners could tune in on any given day to listen to big-band concerts, comedy shows, soap operas and detective dramas, operas, commentaries, sports broadcasts and much more.

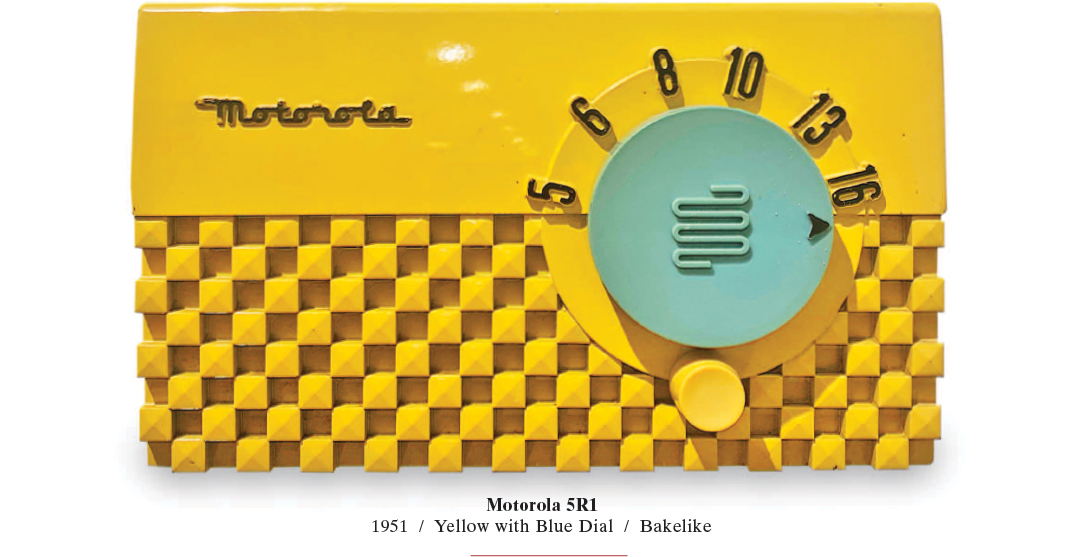

As THE mass medium of the day, hundreds of thousands of radios, in many different styles, were marketed to and purchased by the American public. The physical format of radios evolved, from heavy floor models with wood exteriors resembling a piece of heavy, solid furniture to smaller, lighter versions made of bakelite, and later, the new industrial plastics. The shift to plastics meant the outer shells of the radios could be molded into almost any decorative form, in a wide variety of colors. These lighter, smaller radios could be placed on a shelf or tabletop in any room, so you could move them out of the living room and into the kitchen, bedroom or anywhere you could plug them in.

The current exhibition at the Hilbert brings back a time when there were literally thousands of radio manufacturers in the United States (and all over the world), all competing with one another in a highly cutthroat market. Even the tough economic times of the Great Depression didn’t stop the rise of radio as the most dominant entertainment and news medium, as most people found it an indispensable necessity by then.

Radio was a key lifeline of information for the masses during the World War II years as listeners around the world sat transfixed, hearing vivid reports of battles, victories and defeats. World leaders such as Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill and Adolph Hitler adeptly used the power of radio to influence public opinion.

The Hilbert exhibition features shelf and tabletop radios in a wide variety of styles and varied types of plastic. Bakelite was used for some of the early shelf models, but it only came in muted shades, mostly brown and black, and customers wanted more color. Catalin, a new plastic, allowed for a full spectrum of colors with a resin-like sheen, and Plaskon and other plastics gave rise to red, yellow, blue and other colors. “Marbelizing” the plastics by swirling colors together (often referred to as “onyx” in color choices communicated to buyers) allowed for even more variety.

In efforts to make their particular radios stand out from thousands of other models flooding the market, radio manufacturers turned to hiring many of the top industrial designers in the world to create the sleekest, most beautiful and most desirable radios.

One such designer was Walter Dorwin Teague (1885-1960), hired by the Sparton corporation of Jackson, Michigan to create an elegant Art Deco shelf radio, the Sparton Bluebird, and its floor-model cousin, the Sparton Nocturne.

The Nocturne, an icon of the sleek Art Deco era, cost $350 when it made its debut in 1935—the equivalent of a new Ford car! All its components are hidden behind a striking cobalt-blue mirrored glass disc. This unique radio was manufactured in limited quantities, mostly for hotel lobbies and radio showrooms, and today only a few rare survivors can be found in private collections and museums. The Hilbert Collection’s Nocturne, in near-pristine condition (pictured above), is the superstar of the radio collection. You have the rare opportunity to see it in person during the current exhibition—surrounded by other fascinating radios of the Golden Age.

- - - -

The Hilbert Museum is located at 167 North Atchison St. Open Tues-Sat, 10 am to 5 pm. Admission is free; advance online registration strongly recommended at www.HilbertMuseum.org or 714-516-5880 for more information.