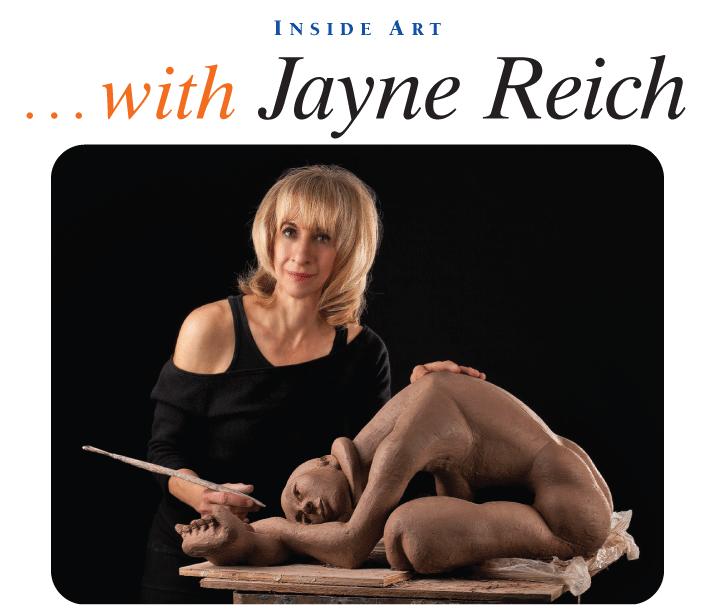

View the work of artist/sculptor Jayne Reich, and while you’ll enjoy the form and figure of each piece, it’s the understanding on a soul level forged between the artist and her model that holds the message. Reich’s art, which doesn’t require and even rejects explanation, represents a melding of human consciousness and unconsciousness that she identifies as a source of living reality.

“The human figure is my passion and inspiration,” says the artist, whose art is widely collected by prominent inpiduals, as well as on display at Chapman University. She works from live models, creating three-dimensional, 360-degree sculptures of the human form. Her extraordinary pieces, with names such as “Limitless,” “Transformation,” “Contemplation” and “Exultation,” invite the observer to experience her art at a primal, gut level.

“The creative process, which is collaborative for me, is deeply intuitive. I begin a piece without knowing where I’m going in order to discover my own inimitable truths,” says Reich, who paints and sculpts and has taught figure drawing, a complete art form in itself, at The Art Students League of New York and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. “I’ve developed a natural style that is an expression of self and as authentic as my signature.”

Intuition at the Heart of Art

It is the nature of intuition and its role in the process of creation that Reich discusses with her longtime mentor, well-known Quantum Physicist Yakir Aharonov, who is a fan of her work. He bought her sculpture “Transcendence,” and honored her by requesting it be placed in the alcove dedicated to him at Chapman’s Leatherby Libraries, along with other priceless items, including his National Medal of Science in Quantum Physics and his Letters of Einstein and Bohm.

“Intuition is at the core of many discoveries by great physicists,” says Reich, who is married to physicist Jeff Tollaksen, Director of the Institute for Quantum Studies at Chapman University. “When Yakir and I discuss the creative process, what comes up repeatedly is how to develop deep and true levels of intuition in order to make new discoveries. For instance, without formal training, Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan, whose life was depicted in the movie, The Man Who Knew Infinity, received while praying flashes of the most complex and amazing mathematical formulas that he wrote on the temple floor.”

For Reich, discovering Aharonov proved synchronistic when she met him in the late 1980s. Her mentor of many years, artist Marshall Glasier, had passed away, and she sought someone beyond the traditional art mentor.

“I had tried studying with many teachers, but, with the exception of Marshall, I found they wished to emphasize technique. Creativity isn’t a technical skill. Art is about your soul—it transcends the mundane and takes on a metaphysical aspect. As Einstein said, ‘Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited to all we now know and understand, while imagination embraces the entire world, and all there ever will be to know and understand.’ ”

The Keys to Creativity

Reich became a student of Aharonov’s when her husband began working with him as a graduate student. “Rather than study physics with Yakir, I looked at the creative process in terms of the geniuses of the world and their use of an incredibly deep level of intuition,” she says. “While doing so, I accessed my true voice and authentic process, and that enabled me to sustain integrity in my work.”

Prior to Aharonov, for 25 years Reich was the assistant and protégé of Glasier, who was trained by renowned German expressionistic painter, George Grosz. “I took my first class with Marshall in New York when I was 19. On the first day, as I sat on a stool with a drawing pad trying to draw a model, he came in and made a beeline across the room. He was a big, clumsy guy and accidentally, on purpose, knocked the stool from underneath me and said, ‘You’ve got to stand up for what you believe in!’ I thought, this is my teacher. He’s talking my language.”

Reich grew up in New Haven, Connecticut, the daughter of parents involved in musical theater. For a time, her father owned a toy company, but it went bankrupt when he died of an aneurism when she was five. For several years, she lived in a segregated housing project surrounded by streams, forests and caves, where she enjoyed spending time.

From a young age, Reich felt an affinity with her great grand-uncle, well-known New York philanthropist Harry Fischel, who helped thousands of Jewish immigrants escape to the U.S. during the war. In another synchronistic turn of events indicative of Reich’s life connected to scientists and physicists, Fischel also happened to be the founder of Yeshiva University in New York and Jerusalem, where her future mentor, Aharonov, taught and founded their physics department. Even more, Reich’s great-uncle, the prominent Rabbi Herbert S. Goldstein, defended Einstein when he was accused of being an atheist communist. Goldstein had an article published in the New York Times that publicly proclaimed Einstein to be a pantheist, who believed in God and was therefore not a communist.

In addition to influencing her artistic expression, Reich’s storied ancestry and experience living in the segregated housing project gave her a keen interest in human rights.

“I’ve always been inspired by people who stand up for what they believe in,” says Reich, who has worked as a life coach, including for celebrities, and lived for many years with Ruth Ellington, sister of Duke Ellington. “During high school, I ran away from home for a couple of days to attend Martin Luther King’s March on Washington when he made his ‘I Have a Dream’ speech. I ended up holding his and Coretta King’s hands. It was the most incredible moment. I’d never met a man who radiated so much love. That experience changed my life and affected my art.”

Perimeter Institute Conference

Last summer, Reich accompanied her husband to the Perimeter Institute Conference of Quantum Physicists in Montreal for a month-long program based on the work of Aharonov. “I fell in love with the sophisticated, sleek design of the institute’s building, including the light and stunning views, and the many chalkboards for expressing creativity,” says Reich, who devised a project during the conference that intersected art and science.

In an impromptu studio, Reich drew 44 collaborative portraits of the physicists and others at the institute. Drawing with chalk on black paper that mimicked chalkboards, she talked with her subjects as she worked. When she finished, they added to the co-creations by including important equations or signatures.

Physicist Lucian Hardy, world renowned for his discovery of “The Hardy Paradox,” was one of Reich’s subjects and commented on the experience. “Art is a powerful way of representing and thinking about reality. Then the artist and subject are part of the process. Each influences the other. Sitting for Jayne was like being part of a quantum experiment, but on the unfamiliar side of the Heisenberg cut.”

Reich follows the same co-creation process when she sculpts. “I always give the model credit, because it truly is a collaborative effort. I let my intuitive energy merge with the model’s so that I bring forth the person’s essence. Most importantly, I want the work to come alive so that I end up with a source of living reality that creates a living eternity.”

Charlene Baldwin, Dean of Chapman University’s Leatherby Libraries, believes Reich’s work accomplishes that goal.

“Jayne’s art is transformative, like her piece ‘Compassion,’ featured in this issue and on permanent display in the Aharonov Alcove. The sculpture personifies the intersection of art, science and creativity, displaying beauty of movement and form. Her living art holds energy and spontaneity and captures the classical figure, while at the same time transcending it.”